Mash of the Titans

- Chris Quilty

- Jul 16, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2025

July 17, 2025 - Written by Chris Quilty

With today’s completion of the SES-Intelsat merger, the era of “The Big Four” is officially over. That’s just the math. But it’s also a sign of something bigger: the center of gravity in satcom has shifted permanently away from GEO incumbents to LEO disruptors. And SES knows it.

To be fair, the decline of GEO’s dominance has been obvious for years. The unraveling has been accelerated by the rise of LEO megaconstellations, stagnating broadcast revenues, and growing demand for mobility, cloud integration, and low-latency connectivity. One by one, the legacy GEO giants have responded in kind:

Telesat is walking away from GEO entirely in favor of LEO with LightSpeed.

Eutelsat absorbed OneWeb to hedge its bets with a multi-orbit move.

UAE-based Yahsat merged with AI firm Bayanat to reposition around analytics and sovereign data.

JSAT is pouring capital into EO and related verticals.

After acquiring Inmarsat, Viasat is now teasing DTD services and other multi-orbit offerings.

SES, Post-Merger: Now What?

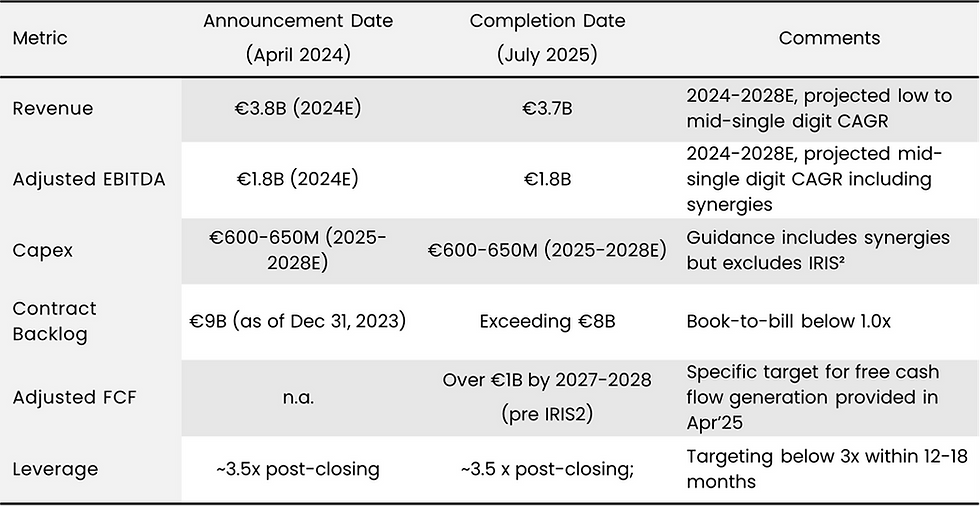

SES may have bought Intelsat, but it didn’t buy time. The new combined company is still projecting modest growth of mid-single digits on revenue and EBITDA through 2028. That’s… respectable, but hardly the stuff that lights up earnings calls in a market racing toward LEO disruption and DTD innovation.

The merger prompted a CFO change, but not a shift in strategic posture. Its near-term priorities are clear: integrate Intelsat, cut costs, and reduce leverage. Longer term, SES must chart a strategy that not only fends off emerging LEO competitors but also accelerates growth beyond its current high-single-digit targets.

Building a LEO constellation to compete with Starlink, Kuiper, or Lightspeed is probably off the table ($10-20B commitment). And an SES-owned MEO constellation in Europe is now called Iris2 – a publicly funded initiative that SES may support but won’t control and is unlikely to generate meaningful revenue for the company before the early 2030s.

SES is eyeing adjacent markets: DTD, IoT, optical networks, SSA, quantum, cloud-based satcom, and AI. Some of these could move the needle later this decade, particularly in areas such as government payload hosting and sovereign infrastructure. Others remain speculative or require long-tail infrastructure bets.

Even with a pristine balance sheet, SES can’t match SpaceX’s financial firepower (est. 2025 capex of $5.5B). Still, SES has other powerful levers: valuable spectrum, orbital rights, landing rights across key markets, and a mature global partner network. These assets position SES to compete in high-value segments, like government, mobility, and managed services, where regulatory moats and long procurement cycles tend to favor incumbents. If deployed strategically, they could become powerful growth catalysts. And with tailwinds from IRIS² and growing demand for sovereign-controlled infrastructure, SES is well-positioned to align with European public-sector priorities as well. Add the right set of strategic moves — deeper telecom alliances, targeted vertical integration, or a Ku-band expansion of mPower — and the merged entity could carve out a credible, differentiated position in a market increasingly defined by LEO, software-defined networks, and multi-orbit flexibility.

Which path SES ultimately takes remains to be seen. But we have no doubt that standing still won’t be part of its journey.